Living Museums is dedicated to history and heritage projects - created with and for young people

SISTER DORA

Sister Dora was a pioneering nurse in Walsall in the 19th century.

She changed people's attitudes to hospitals and medicine - and left a lasting impact on the town.

In the centre of Walsall, there is a statue to Sister Dora, with four reliefs on the base, which show key moments from her life. We have taken extracts from Margaret Lonsdale's biography, which we think might tell the story of these events. Click on the audio files to hear the recordings, read by Jessy Reid (with Jenna Micklewright, Ryan Cheshire and David Allen)

The relievos show: the explosion at the iron works in Birchills, 15 October 1875; the children’s ward (with Samuel Cox, Hospital Chairman); the disaster at Pelsall Colliery on 14 November 1872; and the Men’s Ward (with Dr. MacLachlan).

Walsall in Sister Dora's time

The Sister Dora map has been produced by John Bell, with support from National Drama

Stories of Sister Dora

Here are some stories that show the love people had for Sister Dora.

.jpg)

_page-0001.jpg)

.jpg)

Now click on this audio to hear Diana Wilkes from Walsall, recalling the stories that have been passed down in her family about Sister Dora

When Sister Dora first came to the town in 1865, however, the townsfolk were not so welcoming...

Sister Dora's Thumb: from Centenary of the Walsall Hospital Services 1863-1963)

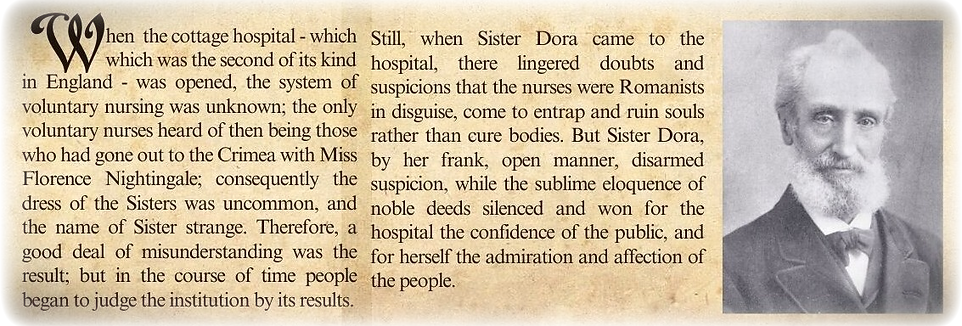

The first Cottage Hospital

The Cottage Hospital opened in 1863 on Bridge Street. Sister Dora came to work there in 1865.

It was the first public hospital in the town; and at first, people were suspicious about it, fearing, among other things, that the doctors would perform experiments on them. Moreover, treatment was free, and there was a widely held view that if something was free, it couldn’t be good...

This is an old postcard of Walsall market. In Sister Dora's time, people could find a number of alternative types of medical treatment on offer.

There was "Ode Texas," for example, also known as Dr. Caitlin, who sold what he claimed were Native American Indian cures. Or his great rival, "Doctor Dick" (Richard Hill) who declared: "I'm Doctor Dick / Who cures you quick / I've a pill for every ill."

A visitor in 1860 called Walter White recalled seeing dozens of stalls

exhibiting an array of glass jars and bottles, some filled with bright yellow liquid, some with various kinds of worms, some with a green substance looking like a preparation of cabbage leaves, some with bullets.

By each stood a glib-tongued orator, vociferating the virtues of his vegetable medicines, extolling the efficacy of his pills (which I had mistaken for bullets) and pointing to the ghastly exhibition of worms as the consequence of neglect of his warnings and recommendations.

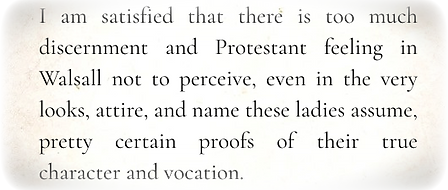

Religious Controversy

There was another reason why the hospital was viewed with suspicion at first. It's summed up by a pamphlet which was written in 1864 by the Reverend Alexander Gordon, called Reasons for withdrawing from all connections with the Walsall Cottage Hospital in its present form. He wrote:

“Puseyism”: a term for the so-called “Oxford Movement” (after Edward B. Pusey), which called for the reinstatement of some older traditions in the Anglican church. Some people feared this was an attempt to move the Anglican Church closer to the teachings and rituals of Roman Catholicism.

The image shows some of the leading figures in the Oxford Movement: Henry Edward Manning, Edward Pusey, John Henry Newman, John Keble, and Robert Wilberforce.

Sister Dora was an Anglican nun; she belonged to the Christ Church Sisterhood (which she joined in 1864). Clearly, the Rev. Gordon thought that the Sisterhood was connected somehow with the Oxford Movement. This, it seems, was partly down just to the way they dressed, and the names they took on when they became “sisters” (“Sister Dora,” “Sister Ellen,” etc.) He wrote:

This is an image of some members of the Sisterhood, taken about 1878.

The Rev. Gordon’s pamphlet may have stirred up local feelings and prejudices. Shortly after she began working at the hospital, Sister Dora fell ill with the smallpox, and she was put in a small room, with a window looking onto the street. The blinds were kept drawn; and a rumour circulated in the town that the room was being used by the Sisters as an Oratory (or chapel) for religious services. Stones and mud were thrown at the window, and people shouted "Idolators!" The Sisters were also shouted at in the street. This is how Samuel Welsh - one of the founders of the hospital - described the events:

This is shown in the following story.

A boy who received an injury was taken to the hospital. One night, Sister Dora found him crying. She asked him what was the matter. At last it came out : "Sister, I shouted after you in the street, 'Sister of Misery!'" "I knew you when you came in," she said; " I remembered your face." But it hadn't stopped her treating him. The boy was amazed...

According to Margaret Lonsdale's biography of Sister Dora, the boy didn't just shout at her in the street - he threw a stone which cut her forehead. But in Samuel Welsh's copy of the book, he wrote the following note in shorthand in the margin: "Not true - the boy shouted but definitely threw NO STONE"

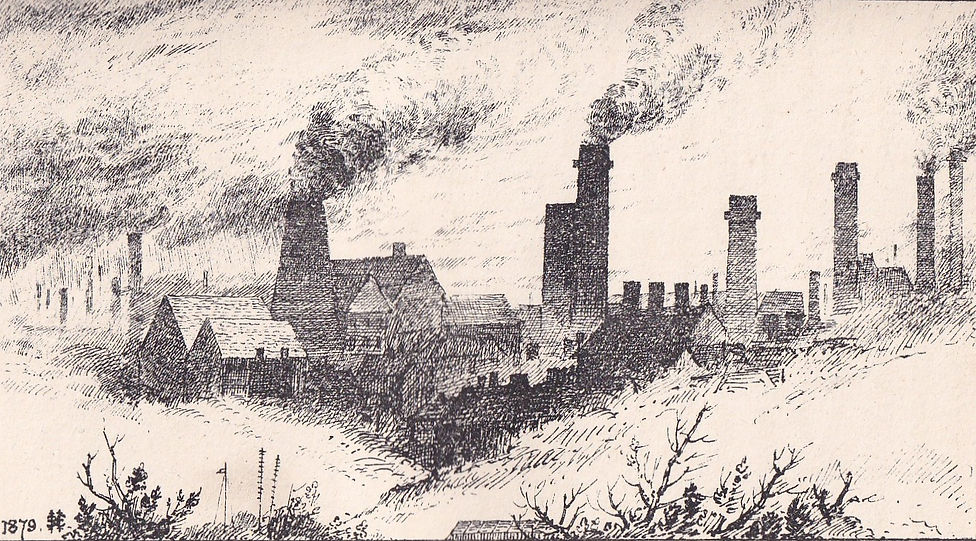

Walsall in the 19th century

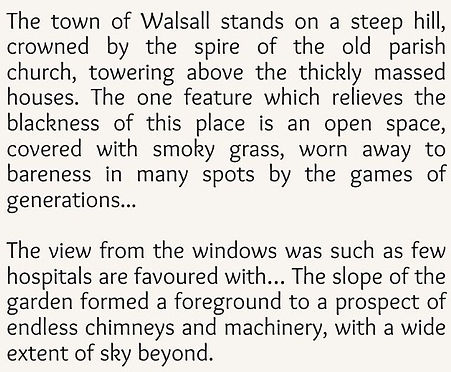

In 1867, the hospital moved to new premises, on a site called The Mount. This image of Walsall appeared in Margaret Lonsdale’s biography of Sister Dora, published in 1880; it is supposed to show the view from the windows of the hospital.

Londsdale herself knew and worked with Sister Dora. This is her description of the town at the time:

George Cotterell wrote a review of Lonsdale's book for the Walsall Observer. He was not happy about the sketch of the town that appeared in the book – or Lonsdale’s descriptions. He wrote:

Lonsdale also described the Epidemic Hospital, in the north of Walsall:

.jpg)

Cotterell commented:

Lonsdale's account of the town, is often how people imagine the Black Country in the 19th century - as a hellish place of furnaces, foundries and fire. But here's a very different image of Walsall - an old postcard of the High Street in 1861.

.png)

Death of Sister Dora

Samuel Welsh remembered what it was like in Walsall on the day that Sister Dora died.

It was Christmas Eve when she passed away, and a dense fog, like a funeral pall, hung over the town and obscured every object a few feet from the ground. Under this strange canopy the market was being held, and people were busy buying and selling, and making preparations for the great Christmas Festival on the following day; but when the deep boom of the passing bell announced the melancholy intelligence that Sister Dora had entered into her rest, a thrill of horror ran through the people, who, with blanched cheeks and bated breath, whispered, "Can it be true?" Although for eleven weeks the process of dissolution had been going on before their eyes, they could not realise the fact that she whom they loved and revered was no more.

Sister Dora Statue

A statue to Sister Dora was erected in Walall in 1886. A ballad was written and sung to mark the unveiling of the statue. Here are two of the verses and the chorus (from The Walsall Observer, 2 Oct 1953)

.jpg)

SISTER DORA GOES TO THE BLACK COUNTRY LIVING MUSEUM

In December 2024, a group of young people from Birmingham Newman University presented a "recreation" of Walsall Market as it might have been in the year 1865, at the Black Country Living Museum.

The idea was to both capture some of the colourful characters of the time, and show some of the “competition” that Sister Dora would, in effect, have faced, in trying to win people’s trust in the new hospital. The different stalls were: Dr. Caitlin; a herbalist; a “necromancer,” inspired by the story of Theophilus Dunn (the “Dudley Devil); a pharmacist (promoting her husband’s new shop on the High Street); and Sister Dora herself, who (we imagined) might come to the market, to tell people about the kinds of treatment they could find at the hospital. There was also a woman who believed in folk remedies, and tried to persuade visitors to carry a rabbit’s foot with them, for luck. The traders did not simply try to sell their own wares, but sometimes denigrated each other’s offerings, too - as market traders often do.

Photos by Kate Green

Creative Commons Attribution for materials on this webpage

Title: Sister Dora

Author: Mantle of the Expert Network

Source: https://www.livingmuseums.co.uk/sister-dora

License: CC BY 4.0