Living Museums is dedicated to history and heritage projects - created with and for young people

Mary Morgan and her world

In 1805, in the town of Presteigne, Mary Morgan was put on trial for the crime of infanticide. She was found guilty, and hanged. She was 17.

It was very unusual in those days for someone to be hanged for this crime.

There are two gravestones to Mary in the churchyard in Presteigne. One reads:

To the Memory of Mary Morgan, who young and beautiful, endowed with a good understanding and disposition, but unenlightened by the sacred truths of Christianity, became the victim of sin and shame and was condemned to an ignominious death on the 11th April 1805, for the Murder of her bastard Child.

The other reads:

In Memory of Mary Morgan who Suffered April 13th 1805

Aged 17 years.

He that is without sin among you

Let him first cast a stone at her

the 8th chapter of St. John, part of the second verse

The two gravestones suggest very different attitudes to Mary and her crime.

Presteigne

This map is from Presteigne Past and Present by W.H. Howse.

It shows the town in 1945 (the year the book was published).

The slide show features images of the town, mostly dating from the early 1900s.

↓ To Maesllwch Castle

We have modified the map from Howse's book, to feature only those things we know were there in 1805. Click on the tags, to hear descriptions of different buildings and locations, and more information about the trial.

KEY

1. Gallows Lane

2. The Warden

3. Radnorshire Arms

4. Town Cross

5. Grammar School

6. Rectory

7. Graveyard

8. Curfew Bell: St Andrew's Church

9. Workhouse

10. The Great Sessions

11. Shire Hall

12. Gaol

13. Lugg Bridge

14. Maesllwch Castle

The Trial

Click on the tag, to hear Judge Hardinge's verdict at the conclusion of the trial

THE MARY MORGAN PROJECT

In 1991, Dorothy Heathcote led a project about Mary with a class of 8 year-olds, in Cape Primary School, Birmingham. Throughout, the children were like detectives investigating a problem: "How can we possibly understand the mystery of how a young woman, under her living circumstances, could kill a small baby?"

Dorothy observed: "And of course, the material sounds a bit horrendous. But in fact, the mystery was looked at through this: two gravestones, on one grave - one seeming to condemn her, and one seeming to forgive her. And we felt this was something the children could handle."

The class teacher was Bogusia Matusiak-Varley. At first, she was concerned about using this topic with 8-year-olds. She said: "I hadn't dealt with death before [in the classroom], and I most certainly hadn't dealt with murder. ... I was just absolutely horrified. I thought: what am I going to do? … What are the parents going to say? How are the children going to take it?"

After the project ended, however, she was convinced that it is only by breaking conventions "that you get the best work". Dorothy commented:

I know everything will work. I know there is no material, based in human ideas and concerns, that will not work, because the teacher plans it carefully, and very tactfully.

As Dorothy observed, the teacher must come to their own decision about working with material like this:

You come back to your own sense of what is right for a teacher to do. I can't advise you, and I certainly wouldn’t presume to advise you. I know that there will be no horror, when I deal with it... There will be the compassion to understand how it might have been for such a lady, under those circumstances. But you make your own choice. The problem is, that frequently, we choose the bland choice; and this makes an even larger separation in children's lives, from what they may see around them, or what they may see on the television - so school seems even more unreal, in the material we present them with. We protect children into experience [in drama]. We don't protect them out of it. We protect them into it. And therefore, we are the judge of what we are prepared to do. We are responsible for our choices. And of course, human affairs range from the most heroic, splendid acts, to the most sordid. And you draw your line where you will.

Quotes from: Making Drama Work: In the Classroom, Tape 1 (University of Newcastle, 1992). You can hear Dorothy talking about the project on the video, above.

CURRICULUM POSSIBILITIES

The project's starting point, then, was two gravestones. They were at the centre of everything - the project circled around them. This could be the basis of other heritage projects for young people: to choose a historical artefact as the centre, such as the Lewis Chessmen, or the Sutton Hoo treasures. The chosen object needs to resonate in some way. In this case, the stones provide a mystery: we do not know who erected the stones, or why there are two of them. We can only speculate.

The stones open up lots of possibilities for curriculum work, for example, in history (life at the time; justice and law; development of industry etc.); but also literacy, artwork, maths, etc. When Dorothy worked on her project, the class teacher was particularly concerned to develop literacy and reading.

THE FICTIONAL CONTEXT

The work was given a fictional context. The children took on the point-of-view of people living in Presteigne. Dorothy herself took on a role, as the new vicar ("The Reverend Heathcote"), arriving to take up her new post.

The children as "citizens" could help the new vicar, showing her round the town - and this would lead, in time, to them helping her to understand the mystery of the two gravestones for Mary Morgan.

So, within their role as "citizens," they would also be "detectives" of a kind.

Dorothy began, in fact, by asking the children if they would like to help her solve a mystery. She asked them to tell her what a mystery is; and what people have to be good at, to solve mysteries.

In effect, she was asking them to think like "detectives" - even within their frame as citizens of Presteigne. She recalled.

I've chosen that as my start. They will never, ever stop detecting on Mary Morgan. And that means they can be trying to be like her, they can watch what happened to her, they can read books about her; but “detecting” is the centre of the whole Mary Morgan work.

In other words: they always found themselves “detecting,” in one way or another, to try to solve the "mystery." The underlying purpose and point-of-view was always: “we look into things.” The children were always looking into things, for meaning and implications.

Following the blackboard discussion, the children were introduced to the two gravestones, that both stand on Mary Morgan’s grave. They read these texts for meaning. In a later task, they looked at documents about Mary's life. Dorothy observed that in the work, "we're always in reading" - i.e., “detecting”:

All the time we are looking at: How do you ask questions, to get information? Not: how do you sit back, and teachers give it to you. What can we initiate ourselves?

Quotes from Making Drama Work: In the Classroom, Tapes 1 & 2 (University fo Newcastle, 1992)

This document was issued to delegates to an event organised by the National Association for the Teaching of Drama. She suggests two other possible frames for the Mary Morgan project:

- for young children: We specialise in church and memorial restoration and employ banker [workshop-based] masons and creative designers for modern requirements eg milestones, fountains, memorials etc.

For older students: We are theatrical suppliers and designers of settings, costumes, properties, anything related with any formal theatre work required by amateurs, except electricals. The latter would require sub-contracting.

These are more indirect ways of approaching the topic than "citizens." There is a play, Mary Morgan by Greg Cullen, which could be used as the basis for work with "theatre designers."

THE MAP: A STARTING POINT

If they were going to be "citizens," showing the vicar round the town, the children needed to develop a sense of the town and the different things in it. As Dorothy observed:

the new vicar … has come to take over a parish about which he knows nothing. So, the children will teach me [in role as the vicar] about the parish; which means I need some strategies so that they’ll know about the parish, before I can be taught about the parish.

So they created a map. She had a large piece of green silk cloth, which she could use to create a map of the village. She also had labels for different buildings, which they could add to the map,

because I must first build the children's ownership of the village. I do not own it. I might sound quite important, you know: “The Reverend Heathcote is coming here.” But it is much more important they own the village.

Labels for buildings included: the butchers, the bank, the garage, the travel agent, etc. Some of the choices laid in possibilities for future work connected with the Mary Morgan story: the courthouse and gaol, the library (which could contain a local history archive), a museum, and so on. Dorothy reflected:

There's this deliberate refusal to want the village the way you'd like it, in me, which is a warning light. It is not my business to say: “Make this village how you want it, but I’ll get it how I want it.” It is not my business. So I can tolerate nothing apparently being anywhere, because it is not my right to want that village, the way I’ve got this dream of how this village ought to be… It's not important to me... The significant areas are the placings by their own will.

On this occasion, then, the children were not asked to produce an accurate historical map - like the one we have featured on this webpage (above). Rather, they chose where to place the different buildings and shops.

This is a decision for the teacher: giving the children the option to create their own fictional version of the town, gives them "ownership" over it. However, you might be concerned, instead, with developing an awareness of the real history of a place - in which case, you could start with a map like the one above, and begin, say, with a sorting task, inviting the children to match the historical photos to the different locations.

You can watch Dorothy working with a group on creating a "map," in the video Dorothy Heathcote at Four Oaks: Monday.

Quotes from: Dorothy Heathcote Video Archive, Tapes 1 & 5 (University of Central England, 1991). Images show Dorothy working on a map with a group of boys, from the video "Dorothy Heathcote at Four Oaks: Monday."

"ARCHIVAL" DOCUMENTS

Dorothy decided that the children would access the story of Mary Morgan through some "archival" documents. These were made to look authentic (i.e., they were hand-written and tea-stained to look old.) They were based on actual documents of the time such as witness statements. In this way, the children were working with "primary" source materials.

The idea was that, in the frame of "detectives," they would explore the materials and make sense of them for themselves. They would be active learners. Nevertheless, Dorothy recognised that the materials might be challenging, in terms of style and vocabulary. But she stated:

Now of course, you come up against your own teaching notions here, of: do you wait, basically, until children are able to do the tasks; or do you use tasks to enable children to become able to do them? Now I work on the latter; if I can find a system whereby advanced work can be achieved earlier, then I do. Because I think it’s daft waiting till children are ready. I think you've got to make them ready; to invite their future, by the challenges you bring. And that means you can't categorise: “That's too difficult.” What you have to look at is: which strategy makes it possible?

Some materials were invented, such as a statement by a carter who took Mary Morgan to the great house, when she first began to work there. These kinds of document had a "more human element to them" (compared with witness statements, for example). (Of course, a historian might question the idea of mixing historical and fictional materials like this; it's a teaching choice.)

These materials would be the main source of information for the children. Making them look old made them more attractive (and more "human") than documents reproduced in books. They were larger than the actual documents would have been, so the print could be larger (and the paper could be looked at more easily by two or more people at the same time). The "aged" effect made them more engaging and inviting to look at. This is an example of what Dorothy called "septic" materials - i.e., they show the human touch. So, there is an extra appeal in the feeling of handling for yourself, documents that have (supposedly) been created by someone in the past; and a sense of discovery: it invites exploration. A standard textbook, on the other hand, is much less inviting. It can seem intimidating - there's a lot of text; and you know it has been produced to teach you something, rather than being something that you can make sense of for yourself.

In this case, the various documents were carefully prepared, to make them accessible to the age group she was working with. If the children had been presented with the original documents in full, this would be too difficult, and the sheer amount of text would be intimidating for them. So the first step was: to carefully select some extracts from the texts - not the full documents.

These materials would be the main source of information for the children. Making them look old made them more attractive - and more "human" than documents reproduced in books.

Here's an example: a witness statement by one of the servants at the house, where Mary Morgan worked. The handwritten version misses the first couple of sentences, so it's incomplete - and this only adds to the sense of a "mystery" which the detectives have to solve. (If the documents are incomplete, they have to work out what might be missing!) But otherwise, the two texts are largely the same:

.jpg)

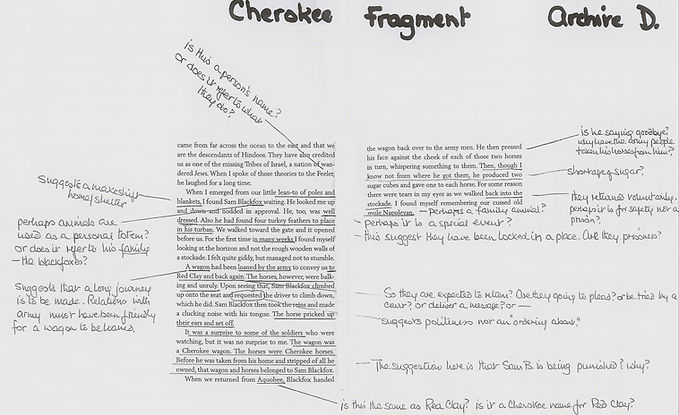

In working with documents like this, one strategy which Dorothy often used, was to make them look as if they had already passed through the hands of an "archivist." The "document" would be pasted on a sheet of paper, and then the archivist's marginal notes and queries were added. Here's an example. In this case, the document was created for a project about the Native American Cherokees. An extract has been taken from "The Journal of Jesse Smoke," a fictional diary of a boy on the Trail of Tears, written by Joseph Bruchac. The text has been labelled as if it has been placed in an archive ("Cherokee Fragment: Archive D"). Notes have been added by hand, as if by an archivist:

.jpg)

The notes do not explain the text, but they help to break it up, and to highlight some things in it, raising questions about it such as: "Is this a person's name?" or "Shortage of sugar?" So the notes act as a guide to reading - without the teacher having to intervene and explain things. They act as "prompts," inviting the children's own speculation, and suggesting possible angles for more investigation and research.

In the Mary Morgan project, Dorothy was working with a group of M.Ed. students. She decided they would be in role as archivists. They began to add notes to the various documents that had been prepared, like the ones on the "Cherokee" document. Dorothy observed:

What we want, is them to take power over the documents, and not be in the power of them…

So she had to consider: “What will empower the children to deal with this?”

Here's an example of the annotations to one of the documents:

To whom it may concern

It is upon my explicit instruction that the tombstone [sic] is to be erected adjacent to the grave of Mary Morgan. I wish those who view her grave shall understand the manner of her death.

Thomas Bruce Brudenhall [*]

Earl of Aylesbury

This document has, I believed, been invented for the project; but it is based in fact.

The gravestone that seems to condemn Mary was indeed commissioned by the Earl of Ailesbury. (*The signature on the document should be: Thomas Bruce Brudenhal-Bruce.)

Notes have been added, as if by an archivist; for example, next to the opening ("To whom it may concern") is a note which reads: "Seems to be an order to someone, not just a letter." Dorothy observes:

To enable a little bit of penetration, I've put some notes on this one; but they are nothing to do with interpreting that. All I've said is: "It seems to be... some sort of order." So I'm just a little bit helping them to see: these words are not just a letter. "To whom it may concern” isn't just an ordinary letter.

This is how she decided to work with the M.Ed. students. She told them:

You are [in role as] the County Archivists, struggling like hell with some documents … and you can make neither moss nor sand [i.e., no sense] of them.

In other words: they would not be the “experts.” They would be people who needed help. As “Archivists,” the students could tell the children that they had done work on some of the documents already, but

you're not sure you’re right. Which allows the children to affiliate with you, and help you. You've already done some, and you'd be ever so glad if they could just help you check it. Which means you can guide them to how to read it, without telling them. And then you can take one [of the documents] that [you say] you are completely baffled by, but you’ve just started on, and let them tell you what to do with the next one.

This strategy "allows you, of course, to watch how to empower them".

She took a document as an example of how she might talk to a group of children, in the role of Archivist:

I look at this, and I say: “There does seem to be a lot here, you see. And some of these words [are difficult]… I think – I’m just wondering: can you see any people?”

.png)

But now, you see, I've spotted [a reference to] “a spotted pocket handkerchief.” Now, that's one I could use to start. “There seems there’s something about a handkerchief here. Do you get the feeling there’s something about a handkerchief here?”

And see what happens… They’ll recognise some of this… [To the children] “Do you get any sense of what's happening? You know, some of these documents are hard, especially when I get a headache. Sometimes, I get a headache, when I’ve worked on them a long time.” It’s that kind of thing.

This is a basic principle of Dorothy’s work: endow the children with expertise. Give them power over the materials, and make them feel they have power to operate. This reverses the standard approach to teaching, where the children feel they have no power.

Source: Dorothy Heathcote Video Archive, Tape A:5 (University of Central England, 1991)

DRAMA EPISODES

The arrival of the new vicar provided the context for the curriculum work. The vicar acted as a kind of "client": the children (as "citizens") were doing things for her. The role provided, then, a "humanising" element.

There were a number of drama episodes: for example, there was a ceremony to welcome the new vicar, and present her with gifts.

In one episode, the children stood as if they represented gravestones in the churchyard. Each of them held an image of a gravestone (which they had created); and Dorothy (as vicar) passed among them. As Dorothy observed, drama

allows us to be one minute gravestones, thinking about being there a long time, and having no eyes; and then we can be people again. Because it's all in the mind. You do it to yourself; and so you can make it happen in your head.

Dorothy decided on a quite indirect way to begin to focus attention on the gravestones. She observed:

A vicar has, by nature of his [or her] duties, to convene, in some way, meetings that matter to the community.

She planned to ask the children to suggest a list of “parish business” - things that need to be decided about in the village. In role as the vicar, she might say to them,

“I’ve found this note on my desk, when I went into the vicarage, that the last vicar says there's been a problem about dogs wandering loose among the traffic. There’ve been one or two near accidents; and I'm just wondering if we should do anything about that, or have a meeting about it?”

If I have one or two what I’d call secular business [issues], that look like you could deal with it quite quickly, [I can say:] “Can we together make up an agenda of what matters to the community, to get done - something done about?” Because that would tell me something more about what interests them about the town.

But my agenda is this business of: “With such a crowded cemetery, and the graves all higgledy-piggledy, and very difficult to read, I wondered whether we could do a cleaning up, so that when people come to see our cemetery, they can see things very clearly? And whether we should preserve the moss and the lichen; and whether we want to do some grave rubbings, and so on, so that people can see how they really read, without having to get down and try and interpret them?”

So that I can hold a parish meeting, and myself be very puzzled about the two gravestones … which allows me to get into the question of: “I don't understand this - why this person has two gravestones - why the name ‘Mary Morgan’ is on two.”

It all seems very casual and ordinary - making it seem as if the problem or issue was “bred” by the context, and emerged almost by chance.

This kind of indirect approach is a way of catching children “off-guard,” so they become interested and immersed in a topic, and want to know more about it – without feeling they are being forced to learn about it.

Crucially, it means that the children feel that they have power over what to do - rather than being told what to do by the teacher.

The questions raised about the gravestones in the "parish meeting"

would lead me, naturally, to the Archives.

So there was a kind of developing "storyline," where one episode led naturally to another.

In the first video, David Allen discusses the Mary Morgan project. In the second. Bogusia Matusiak Varley recalls working with Dorothy on the project

Creative Commons Attribution for materials on this webpage

Title: Mary Morgan and her world

Author: Mantle of the Expert Network

Source: https://www.livingmuseums.co.uk/mary-morgan

License: CC BY 4.0